I’ve always preferred the writers I discover on my own to the writers others—be they teachers or friends—recommend to me.

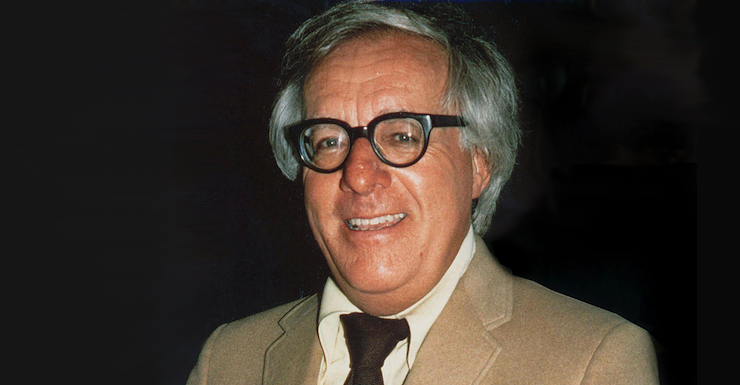

Ray Bradbury is one such writer.

More than that, he’s one of my literary heroes, one of the authors who inspired and solidified my desire to be a writer. And I’m hardly alone—within the SF community, he’s one of a handful of iconic authors most often cited as an influence and a favorite, and many non-SF readers frequently cite him as their gateway into the broad genre of Speculative Fiction.

Yet, some readers find Bradbury difficult to approach.

In some cases, this attitude stems from an academically-instilled snobbery around SF that still exists in some circles (which, I’m happy to say, seems to be gradually fading away). For others, though, it’s simply a matter of sheer volume.

Bradbury was a prolific author (not Isaac Asimov prolific, but prolific). For young writers starting out in the era where the only venues for SF were in the pages of pulp magazines that paid half a cent to three cents a word, the ability to produce a lot of work relatively quickly was necessary for financial survival. Short fiction, in its many variations, became Bradbury’s primary medium, and in the process, he became a master of the form.

Once, however, he’d crossed over into writing for the “slicks” and publishers starting putting out SF in book form, Bradbury was able to turn his hand to other forms of writing—novels, story-cycles, stage plays, screenplays and teleplays, and essays. Eventually, he became sui generis—unique, a genre unto himself—as the best writers do.

Every upside has its downside, of course: Because of the sheer quantity of writing he produced, it’s hard to recommend a single Bradbury work to someone that’s unfamiliar with his oeuvre. Readers are individuals with subjective preferences. Some people love long fiction, hate short fiction. For others, it’s vise-versa. Some tend to avoid fiction all together and are more interested in nonfiction. And again, for others, it’s the opposite. So where can you point them in terms of Bradbury’s work?

Well, here are a few suggestions to keep in mind that cover the spectrum…

Long Fiction: Fahrenheit 451

(This one’s obvious).

Many readers first find their way into Bradbury’s work via the rabbit hole provided by one of his novels—he wrote eleven of them in total. Four other popular routes include The Martian Chronicles (my own first Bradbury book), Something Wicked This Way Comes, The Halloween Tree, and Dandelion Wine, all of which are great ways to encounter Bradbury for the first time.

However, my personal favorite is his dystopian, soft science fiction classic, Fahrenheit 451.

The opening sentence alone is a masterful invitation to keep reading: “It was a pleasure to burn.” It’s up there with “It was a bright, cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen,” in the Great First Line Hall of Fame. Why is that? Because like all great first lines, it raises a number of questions for the reader, piquing one’s curiosity. Immediately, it makes one wonder, “Why is it such a pleasure to burn?”, “Who is feeling this pleasure?”, and of course, “What, exactly, is being burned?”

As soon as you ask those questions, you enter into the domain of Guy Montag and his technology-addicted, book-hating society (a vision that seems only to grow more prescient as time passes).

The novel gives you a taste of Bradbury’s rhapsodic style in long form, with one of the best examples being the first paragraph, following on from that superb opening line:

It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things, blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history.

In addition, Fahrenheit 451 offers readers an introduction to many of the key themes that recur throughout his science fiction: A suspicion towards technology. The addictive power of machines of convenience and entertainment. Anti-anti-intellectualism (for lack of a simpler term). Anti-individualism. And, of course, the emotional power of the printed word.

Any of Bradbury’s longer narratives would be a good choice, if novels are your thing. However, if you want general insight into what his work is at its best, I recommend starting with this, the novel which made him a household name.

Story Collection: R is for Rocket

(This one might be a bit of a surprise).

Short stories were the form where Bradbury did much of his best work and clearly the form in which he preferred to write most often. He produced eleven novels, many of which were fix-ups of earlier short stories, while he produced between 400 and 600 individual short stories. (That’s between 37 and 56 short stories produced to every novel, if you’re interested).

As with his longer works, any of his short story collections serve as excellent potential starting points. Four of his better known collections include The Illustrated Man, Medicine for Melancholy, The Golden Apples of the Sun, and The October Country, and contain the core of his most iconic stories.

My personal recommendation, however, is the collection titled R is for Rocket.

Bradbury published this particular collection back in 1962, specifically for a burgeoning new book audience: Young Adult readers. He intended it as a greeting card to young readers of SF as they were aging into the adult sections, saying, “Hey, if you like these stories, check out my other books when you’re old enough.” And what a greeting card it is…

Rocket takes some of the best stories from all of the aforementioned collections and places them into one book. Such classics include “The Fog Horn,” “A Sound of Thunder,” “The Long Rain,” “The Exiles,” “Uncle Einar,” “Here There Be Tygers,” and “The Dragon.” Additionally, the final two stories featured—“The Time Machine” and “A Sound of Summer Running”—are tales he eventually incorporated into his novel Dandelion Wine. It’s the literary equivalent of a sample platter.

The one downside is that this book is rather difficult to track down. It’s currently unavailable as an eBook, and most of the paperbacks in the wild are rather tattered. But, if you can find a copy (I found my personal copy in a used bookstore), it’s well worth adding to your library. If not, all the stories remain available in their original collections, so you can still enjoy discovering them all!

Short Story: “Homecoming”

(Granted, it might seem odd to pick a short story that’s not included in my collection of choice, but it’s my choice, after all…)

Picking one Bradbury short story to recommend as a starting point is like trying to decide, once and for all, who your favorite author is—there are just so many great options. The one I’ve selected, however, is one any reader can find in one of his most famous—and readily available—story collections, The October Country. It’s titled “Homecoming.”

The story of its publication is one of the great literary anecdotes in history. Dorothy McIlwraith, the editor of Weird Tales during the 1940s, turned down the story. Bradbury, taking a gamble, then sent his tale to Mademoiselle, a popular women’s magazine that published fiction. While it sat on the slush pile, another young writer working there at the time read it, thought it was good, and told the fiction editor to publish it. That writer was Truman Capote, author of In Cold Blood and Breakfast at Tiffany’s. And with that, the story became one of Bradbury’s earliest breakout works as he moved from the pulps into the slicks.

What makes it so great, though?

Imagine if you watched the old TV show The Munsters through the point of view of Cousin Marilyn—who, unlike her supernatural relations, is a normal, all-American human—except that, in this version, she’s a boy who longs to be like her family. That, in a nutshell, is “Homecoming.” Except my ridiculous synopsis really doesn’t do justice to this story. It’s a melancholic examination of those universal childhood feelings: the desire to belong and the hatred of being different. Through Timothy’s eyes, we look closely at the Elliot family—a clan composed of witches, warlocks, vampires, and other creatures of the night—and we come to understand his feelings, his longing to be like them. Yet, at least within the confines of this story, he never has his desire fulfilled.

This story, for me, illustrates the intense emotional power of which Bradbury was capable, both within Science Fiction and outside it; his ability to evoke and explore feelings and desires that inspire empathy and resonate so profoundly with readers. That potency convinced Capote—who’d rise to the top of the ranks among New York’s literati—that Mademoiselle should publish it. That quality makes “Homecoming” one of the best examples of his craft in the short form and ensures that his work still resonates with people today—a perfect starting point for any tenderfoot reader.

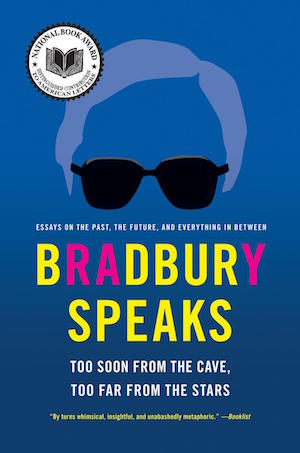

Non-Fiction: Bradbury Speaks

(If none of my previous selections worked for you because you don’t read fiction, or don’t want to start with fiction, then this one’s for you.)

Most avid readers know Ray Bradbury for his fiction. Yet, in the later part of his long career—much like fellow SF writer Isaac Asimov—he turned his hand to other forms of writing. He published a collection of poetry. He adapted several of his works—short stories and novels—into teleplays, screenplays, and stage plays. And, of course, he wrote numerous essays on a variety of topics.

Likely, to would-be writers, Bradbury’s best-known nonfiction collection is his famed Zen in the Art of Writing, a compendium of pieces—essays and poems—on the subject of writing. Certainly, it stands next to other great books on that theme, like The Elements of Style by Strunk and White and Stephen King’s On Writing. But its subject matter is, by necessity, limited.

Simply for the broader selection of topics covered, Bradbury’s late essay collection Bradbury Speaks: Too Soon from the Cave, Too Far from the Stars is a better choice.

The title tells you exactly what you’re getting. The collection contains various essays on a number of topics that were close to Bradbury’s heart: writing, Science Fiction, famous people he knew and loved, life (in general), the city of Paris, and the city of Los Angeles. However, relatively few people know of this book, and those who do often don’t rate it highly within the Bradbury canon (look no further than Goodreads for evidence of this). This is in part because it is nonfiction, which Bradbury wasn’t known for producing.

In his introduction, he directly points out the disparity between his public reputation and the book’s contents. In spite of audience expectations, though, he also explains his commitment to the essay as a form, why he writes them, and how he approaches them:

Although I suppose I am best known to readers as a fiction writer, I am also a great lover of the essay and have written hundreds of them. Everyone has heard of the “familiar essay,” in which the writer draws on personal life experience, ideas, and the world around him. But few know the term “unfamiliar essay,” where a god-awful amount of research has to be sweated through. All of the pieces in this book are familiar essays. I’ve written only one unfamiliar piece. […] All of my other essays were born of explosions of love and quiet passion. (Bradbury Speaks, 4-6)

And the pieces reflect that quiet passion. A connecting thread, tuned perfectly to the pitch of enthusiasm, runs through the whole collection. Each piece rises out of great depths of Vesuvian love for his subject matter. Inaddition, Bradbury manages something in these essays that only the best essayists achieve. If you listen to Bradbury actually speak (in a tribute here on Tor.com, Leah Schnelbach suggests An Evening with Ray Bradbury as a useful way to get a sense of his voice and presence), and then read these essays, you’ll see that they perfectly capture his speaking voice and rhythms. Reading these pieces makes you feel as if you’re being personally addressed, somehow—as if the author’s in the room with you, revealing his thoughts directly to you and you alone.

That same rhapsodic quality that you find in his fiction remains present in his nonfiction, but it’s slightly transformed. With each new literary form comes new requirements. Bradbury’s fictional prose is heavily metaphorical, boarding on the metaphysical at times. His nonfiction retains the same passion, but aims for greater clarity in the service of communicating his ideas. The composer is the same; only the key in which he composes is different. If this collection is the place you choose to start your journey with Bradbury, you’ll still hear the music of his words.

No matter where you begin with Bradbury, though—be it one of the suggestions listed here or another book or story—his work and the music of his words will enrich your life. They can entertain you. They can inspire you. They can make you think and, I’d argue, more importantly, they can make you feel. So pick a point and let his voice into your world.

If you’re interested in letting more of Ian Martínez Cassmeyer’s voice into your world, check out his Twitter feed and his blog, Ian’s Two Cents.